Insight Report 1 – Part of The Future is Peer series

Peer Support in Scotland is a new Insight Report from Scottish Recovery Network. It makes the case for peer support as a core component of a recovery focused, people-led mental health system.

The first in a four-part series, it draws on evidence, lived experience and national and international data to show why peer support matters, where we are now, and what action is needed to ensure peer support is not an optional add-on, but central to delivering Scotland’s vision for mental health recovery and wellbeing.

The reports are part of a programme of work to champion peer support and peer working in mental health as set out in Strategic Action 2.3 in the Scottish Government and COSLA Mental Health and Wellbeing Delivery Plan.

- Download the full report as a PDF or flipbook

- Download a summary version (PDF)

- Read the report in sections (below)

If you need this report in a different format, please get in touch

We have come a long way…but I feel there is much room for expansion in our field of expertise.

Peer worker, Bipolar Scotland

Peer Support in Scotland is the first in a series of four Insight Reports. It is intended as a foundational report and will set out:

- What we mean by peer support in mental health

- Why peer support has a key role in mental health recovery

- Existing peer support activity and workforce in Scotland

- Drivers and opportunities for peer support development in Scotland

This report will be followed by Insight Reports 2 and 3 which will focus on the role of peer support in prevention and early intervention, and in crisis and distress. The reports will include examples of peer support in action in Scotland and further afield. The fourth Insight Report will focus on the enablers and barriers to growing peer support in Scotland sharing Scottish and international evidence of what works.

Our recent Growing Peer Support in Scotland Community Roundtable discussions highlighted the desire for the creation of a community-led mental health system focused on relational, human approaches to support and recovery.

This radical vision is also one supported by government with the commitment to health and social care that is ‘people-led and value-based’. Achieving this transformative vision requires new thinking, new perspectives and new solutions. A much more significant role for lived experience leadership in designing and delivering the new future and for peer support to be an equally valued and integral part of our mental health system.

We want to thank all the people, groups, organisations and services across the country who continue to share their peer support learning, views, practice and innovation. Showing what’s possible when the knowledge and skills of people with lived experience are valued and invested in. We also want to acknowledge key people who have supported Scottish Recovery Network in our journey to produce these reports, particularly Ruth Stevenson of Ruthless Research, Callum Ross and Lisa Androulidakis of Habitus Collective and Dr Simon Bradstreet of Simon Bradstreet Consulting.

The Future is Peer.

Louise Christie, Director, Scottish Recovery Network.

We believe that by working together, Scotland can be a place where people expect mental health recovery and are supported at all stages of their recovery. Our work brings people, services and organisations across sectors together to build a mental health system powered by lived experience and strengthened by peer support.

Scottish Recovery Network has a strong track record of promoting and supporting the development of peer support and peer worker roles in mental health. This has included:

- Connecting those involved in peer support

- Showcasing innovation and sharing learning through events and communications

- Developing and using resources to support the growth of peer support and the training and development of peer workers

- Providing mentoring and development support to people, groups, services and organisations growing, sustaining and expanding peer support

We strongly believe, and our networks and partners tell us, that the development of peer support is a two-fold opportunity:

- Developing peer support is a way to transform culture and practice in mental health services. Embracing an approach focused on the whole person, which is trauma responsive, human rights based and supports recovery

- Peer support can play a significant role in improving peoples access to, experience of, and positive outcomes from mental health services and supports

In writing this report we drew on a number of sources. As such, our findings and recommendations are informed by Scottish experiences, opinions and practices as well as by international experiences and a broad range of published research:

- Learning from our extensive work with those developing, delivering and participating in peer support across Scotland and further afield

- The Big Scottish Peer Support Survey, commissioned by Scottish Recovery Network in 2024 to improve knowledge and understanding of peer support activity and workforce

- The discussions and findings from three Growing Peer Support in Scotland Community Roundtables held in February and March 2025. These participatory events brought people and organisations across sectors together to identify what is needed to grow peer support in Scotland

- Peer Support Without Borders (2025), a review of international approaches to developing peer support in health and social care systems (with a particular focus on Canada, Denmark, England, Aotearoa New Zealand, Republic of Ireland and Wales) commissioned by Scottish Recovery Network

- Analysis of academic research on peer support

Peer support is widely acknowledged to be an integral part of a recovery promoting mental health system (World Health Organisation, 2022). What do we mean by mental health recovery? This short Let’s talk about recovery animation gives and overview.

Anyone can experience mental health challenges but with the right support people can and do recover. Recovery means being able to live a good life, as defined by you, with or without symptoms.

When considering mental health recovery, we acknowledge that it is not necessarily easy or straightforward. Many people describe the need to persevere and to maintain hope through the most difficult times. There are two core elements to a recovery approach:

- A fundamental belief that everyone has the potential for recovery – no matter how long term or serious their mental health challenges

- It’s based on learning directly from lived experience – people in recovery, or who have recovered from mental health challenges

A recovery approach is different from that of traditional or clinical mental health services (Anthony, 1993). Instead of a starting point of a patient with something wrong with them, a recovery focused approach starts with the person and their life. It explores who they are, what’s happened to them, what’s important to them and what they want for their future.

Specific treatments and therapies may alleviate symptoms but this is only part of a recovery approach. It should include the opportunity for people to build on or reignite their strengths, skills and interests, facilitating the support elements and networks needed. The primary goal in recovery is the person living the life they want (Repper & Perkins, 2006).

There is a wealth of research that confirms that relationships are central to recovery and to the experience of mental health services (see for example, Davidson et al, 2005). Experiencing relationships with mental health workers who understand, respect and believe in you enables people to hold onto hope, believe in themselves and their own possibilities.

Peer support approaches are a key component of a recovery focused system and can contribute to creating the conditions for recovery promoting relationships to flourish. Peer support is inherently non-clinical. It is based on lived experience and mutual relationships rather than diagnosis and symptom management.

Being a mutual relationship rather than a clinical intervention means that the approach can be grounded in empathy, providing space and time for the person to be heard, understood and validated. This enables a different type of conversation which is led by the person rather than by the requirements of assessment, diagnosis and monitoring.

Acceptance and understanding of mental health recovery has increased significantly in Scotland but translating this into policy and the design and delivery of mental health services, particularly statutory services, has been more challenging (Gordon & Bradstreet, 2015). Embedding mental health recovery into policy, service design and delivery means shifting our perspective. We need to move away from what we do currently (more of the same) to embracing lived experience leadership. This will allow us to better understand what supports recovery and make the transformational changes needed to make our mental health system fit for purpose. It will also help ensure that recovery, which is prone to misappropriation and abuse (Slade et al, 2014) remains true to its founding values (Owen, Watson & Repper, 2024).

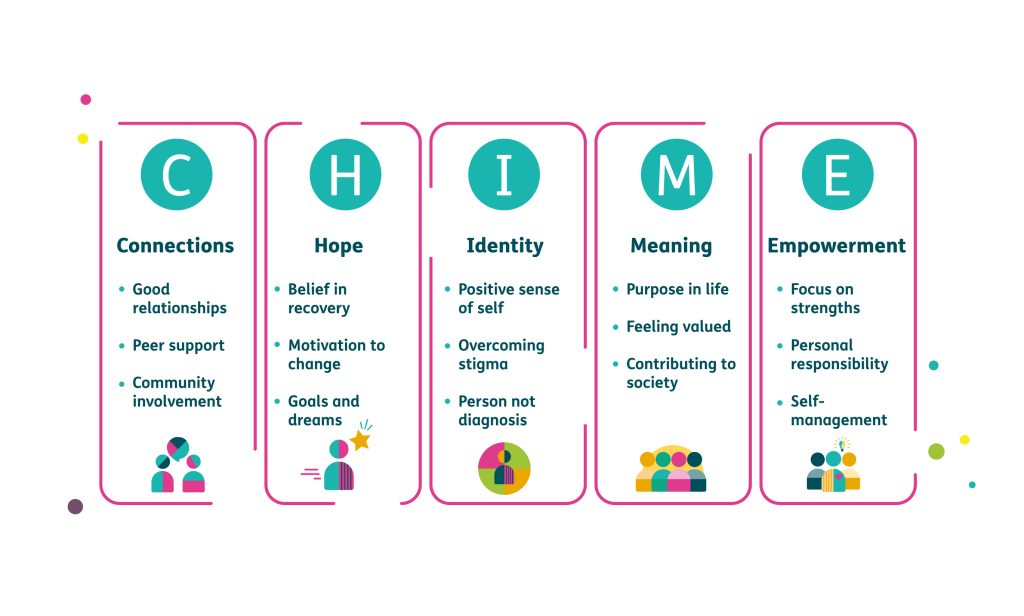

While recovery is a personal journey common factors or themes have emerged from the sharing of lived experience through practice and research. The CHIME framework for personal recovery in mental health (Leamy et al, 2011) is widely recognised and commonly used in Scotland and internationally.

It highlights the importance of connections including shared experiences, the need for hope, the importance of a positive sense of identity and meaning and structure in life as well as a strengths-based approach which fosters empowerment and agency.

We do know from our, and others extensive engagement with lived experience that recovery is best supported by approaches which focus on the whole person, are relational and where lived experience is embedded, such as by having peer workers or facilitating access to peer support opportunities.

Peer support is a mutual relationship where people with shared lived experiences support each other particularly as they move through challenging times. It has been described in the following ways.

A powerful way for people experiencing mental health challenges to connect with others who really understand what it feels like. (Stevenson, 2025)

Offering and receiving help, based on shared understanding, respect and mutual empowerment between people in similar situations. (Mead, Hilton & Curtis, 2021)

Walking alongside someone who understands, who ‘gets it’ helps people to feel less alone. It offers them the opportunity to explore their feelings, gain insight and learning and identify what will help them live the life they choose.

There is a great deal of strength gained in knowing someone who has walked where you are walking and now has a life of their choosing. (Scottish Recovery Network, 2013)

This report is focused on formalised mental health peer support such as:

- Peer support groups whether in-person, online or digital

- One-to-one support for people experiencing distress and crisis, for those seeking help to manage their mental health and wellbeing and for those seeking support to continue their recovery journey

- As a listener, navigator and connector in community hubs and other first points of contact including supporting people to identify and access local opportunities and activities that improve their mental health and wellbeing

- Peer-led recovery education and self-management

Peer support can be delivered in many different ways but all are firmly rooted in hope, shared experiences, mutuality and supportive, intentional relationships. We refer to those delivering peer support as peer workers, whether paid or unpaid. Peer workers are people with lived experience of mental health challenges who are trained and employed to use their lived experience intentionally to support others in their recovery journey. This shared lived experience enables peer workers to instil hope, model recovery and support people as they work to reclaim a meaningful life of their choice.

Peer support is a force for change

Peer support has its origins as a social movement challenging attitudes and discrimination (Davidson et al, 2012). Like other social movements it is about self-determination, human rights and rebalancing and sharing power. These powerful roots mean that peer support can be a force for change in our communities but can also make a significant contribution to changing the way we design and deliver mental health services.

…peer support can be a force for change in our communities but can also make a significant contribution to changing the way we design and deliver mental health services.

(Habitus & Scottish Recovery Network, 2025)

Peer support has developed in Scotland and other countries as a response to mental health systems and practices which resulted in people feeling misunderstood and often misjudged and mistreated (Mead, Hilton & Curtis, 2001; George et al, 2016). Through peer support, people living with mental health challenges are seen as part of the solution. They have a significant and active role to play in supporting their own recovery and that of others.

When I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder 30 years ago there was no such thing as a peer support worker. If I had had access to one back then my recovery would have been quicker and less solitary and stressful. We have come a long way since then, but I feel there is much room for expansion in our field of expertise.

(Peer worker, Bipolar Scotland)

In 2021 an evaluation of the Peer Support Test of Change for East Renfrewshire Health and Social Care Partnership highlighted the value of mental health roles grounded in shared lived experience and mutuality. The evaluation reported clear evidence that the peer relationship and sharing of lived experience enabled different types of conversations. Conversations which open up opportunities for people to embrace changes in thinking and action to improve their mental health and wellbeing.

People value working with someone with lived experience because it helps them develop a sense of clarity and reflection on their own experiences. There is a strong sense of validation in the peer relationship which creates opportunities for change. (Bradstreet & Cook, 2021)

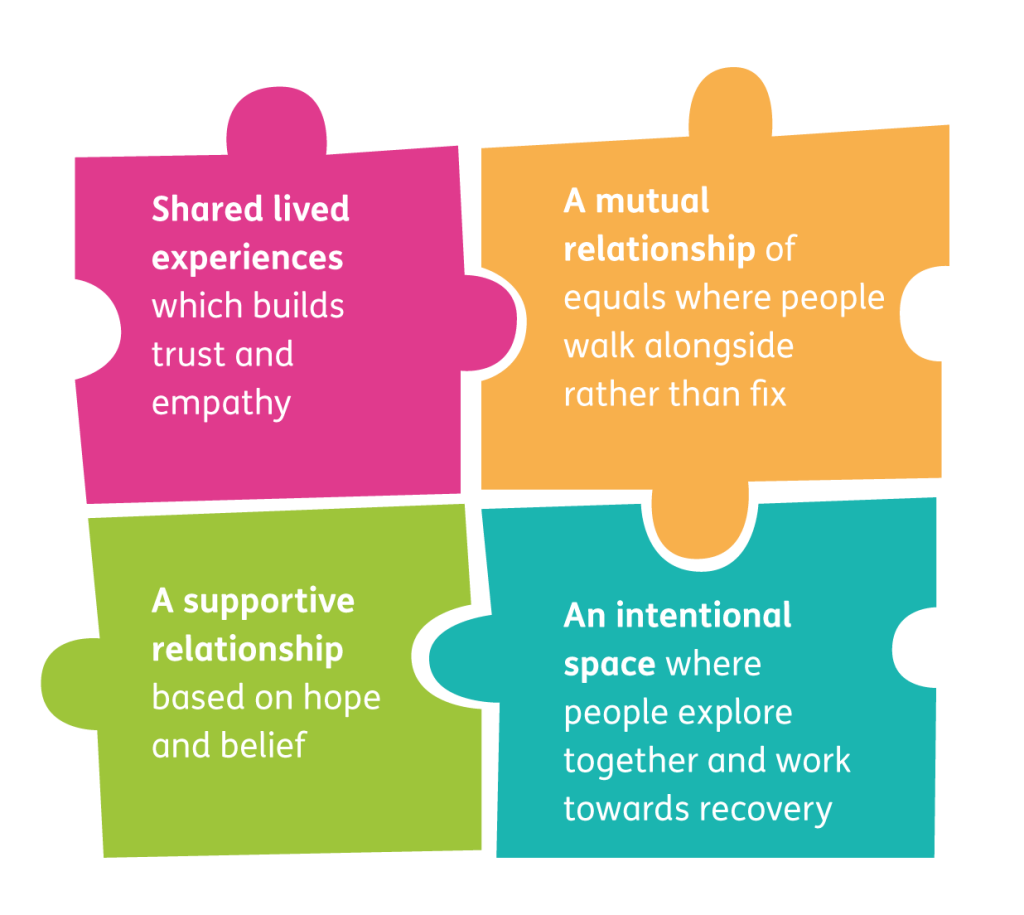

In 2021 Scottish Recovery Network asked people across Scotland about peer support and what it means to them. Through a series of events, meetings and discussions they told us that peer support has four key components and that all need to be present:

Shared lived experiences

The peer relationship builds trust, empathy and hope through shared experiences and personal connection. Peers are evidence of recovery, instilling hope that things can and will get better.

Peer support is a whole person approach based on the person and their life experiences rather than solely diagnosis. Having someone who understands means that people are more open and honest. It also validates people’s feelings which helps them to find meaning in them rather than hide them and feel shame.

It kinda gave me, in a sense, comfort in a way because you know…this person you know has been coping with similar things and could really understand.

(Bradstreet & Akisanya-Ali, 2022)

There is a strong sense of validation in the peer relationship which creates opportunities for change. (Bradstreet & Cook, 2021)

It’s important to note that peer support is not just about telling your story but using your lived experience intentionally to support someone to explore their experiences and find their own recovery path. The peer role is as a coach or mentor rather than fixer. This shared experience and openness also provides people with assurance of not being judged but being understood. Of not feeling alone but connected with others in a meaningful way. Peer support creates spaces free of stigma and opportunities for people to address self-stigma.

It’s the only thing that really changes people’s lives in the long term! Connecting with others who know the path you’ve been on is life changing.

(Stevenson, 2025)

Peer support is especially impactful for diverse communities because it offers flexible, culturally relevant, person-centred support. Unlike many traditional services, peer support adapts to cultural values, language, and community-specific needs. It also means that the experiences shared can be wider than what we often think of as mental health and wellbeing. Recognising the huge impact of issues such as poverty, gender-based violence and racism on mental health and the experiences of discrimination that many people face.

A mutual relationship

Peer support is a strengths-based approach which explicitly values lived experience. Where the relationship brings insight, learning and recovery for both or all involved. It is about ‘walking alongside’ the person rather than fixing, fostering a partnership of equals.

The peer relationship acknowledges that all have a contribution to make and learning to gain. Starting from the person and their life, the peer relationship explores people’s assets as well as their challenges. This enables them to find or refine their strengths, skills and passions and draw on them as part of their mental health recovery journey. The role of the peer worker is to ensure that the power and dynamic boundaries of this relationship are managed and equal.

We have endless examples of the amazing work of peers, the impact it has not just on participants but of those providing it – it’s a win-win.

(Stevenson, 2025)

In the peer relationship the focus is on empowering people to view themselves as a central agent of their own recovery. Through peer support we work together towards recovery, supporting people to self-advocate, understand, and use their own agency to make informed choices.

Central to the peer relationship is preserving and enhancing the autonomy and decision-making capacity of people supported, even in times of crisis or when people are subject to coercive measures.

A supportive relationship

Peer support recognises the importance of connection and relationships in recovery. The peer relationship is just that – a relationship not a clinical intervention. Peer workers not only embody the reality of recovery; they also hold space for others, offering hope even in someone’s lowest moments. By listening with empathy and supporting the person to explore and identify what they want to do, peer workers enable people to find their own path. A path that includes a combination of things that help them live well. In the peer relationship the peer worker will ensure that, at all times, they use language that is inclusive and recovery focused, for example, exploring what’s happened and what is possible, not what is wrong.

This supportive peer relationship is based on the understanding that there is no one way to recover. It is strengths-based and rooted in a belief in lived experience. People know themselves best but can need help to understand what recovery looks like and what works for them. It is not directive or prescriptive. It is about the person and what they need, not what the system or bureaucracy decides is important and can be provided.

An intentional space

Peer support is a collaborative space where people come together with the purpose of exploring and learning so they can move towards mental health recovery together. The sharing of experiences of mental health challenges and recovery means that people can learn from and be inspired by others.

The peer support relationship whether group or one-to-one is warm, kind and friendly but is not friendship or befriending. It is a space designed and managed to enable the person to identify what is important to them. To support them to identify their goals (the life they want) and what needs to happen to move towards them.

While peer support may look informal on the surface and be experienced as informal it is underpinned by mutuality and intention. This is often expressed in, for example, group agreements or through shared action plans but in all cases the relationship is primary and is negotiated and managed by those involved.

A chance to talk and not feel alone in their anxiety and stresses, a chance to learn from others who have gone through similar experiences and learn how they got through it.

(Stevenson, 2025)

In this short film The Neuk Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Centre, in Perth, share their intentional approach to crisis intervention.

They emphasise the advantages of a non-clinical setting in helping people feel welcomed and not judged. They are also clear that The Neuk as a space is not owned by or run for the staff but for the people seeking help there. People are encouraged to make themselves at home and given space and time to move on from high levels of distress. During this time team members sit alongside people listening with empathy. Once the person is able, they will discuss immediate safety with them and then, if possible, ensure they get home safely. In all cases there is a firm arrangement to return, mostly the next day, to continue safety planning and identify what will help the person to move forward in their recovery.

Scottish experience and views on the core components of peer support are validated and supported by published research literature. Most, but not all of this literature relates to peer support working where peer support workers have been described as a ‘liminal space’ between services and people supported by them (Watson, 2017).

This space may allow for stronger early connections to be formed from which recovery opportunities are more likely to emerge and be explored (Bradstreet & Akisanya-Ali, 2022). In other words, a key mechanism of how and where peer support works is likely to be the different type of relationships that exist between peers compared with typical professional – service user/patient relationships with their inherent power differences (Watson, 2017).

Other perspectives suggest that peer support provides an important space for people to reconsider identity and to understand the nature and impact of cultural forces that can encourage people to adopt identities of illness. This understanding builds capacity for “personal, relational and social change” (Mead, Hilton & Curtis, 2001).

Solomon (2004) extends this by highlighting how peer workers’ experiential knowledge enables them to model alternative identities and recovery pathways, demonstrating that a meaningful life is possible despite mental health challenges.

Based on an extensive systematic review of peer values and expert consultation, Gillard and colleagues (2017) identified five principles of peer support which resonate with the experiences and priorities described earlier:

- Relationships based on shared lived experience

- Reciprocity and mutuality

- Validating experiential knowledge

- Leadership, choice and control

- Discovering strengths and making connections

This framework is underpinned by Solomon’s (2004) foundational work which identified experiential knowledge as the defining mechanism of peer support, emphasising how shared lived experience creates unique conditions for authentic relationship building and mutual benefit through the helped therapy principle.

Peer support is often familiar but not fully understood. This has led to some common myths or misconceptions resulting in peer support being under-recognised and undervalued. They inhibit the potential for peer support to be seen as part of the change needed in our mental health services and supports. Common myths include:

Peer support is risky

Risk is inherent in all types of mental health treatment and support. There is risk when taking medication, when sitting on waiting lists and there is risk of

misdiagnosis. Why is the risk associated with peer support treated differently? Peer support takes a peer relationship and formalises it with boundaries, values and a way of working that protects everyone involved.

While there is a need to improve adverse event reporting in research related to peer support (Pitt et al, 2013) from available evidence we know that peer support is no more risky than non-peer interventions (Yim et al, 2023).

Peer support is just telling your story

Appropriate training and supervision enables peer workers to know when and how to use their lived experience in a way that maintains mutuality and supports mental health recovery. Peer workers do not tell their story but use their lived experience of recovery with the intention of supporting others.

Evaluations of peer support training suggests that while training people in the intentional use of lived experience is complex it is typically a core element of courses (Simpson et al, 2014; Bradstreet & Buelo, 2023).

Peer support is friendship and a chat

Peer support is a structured, intentional, goal-orientated relationship – with clear boundaries – focused on recovery. It is based on shared lived experiences and shared power rather than just social connection. Peer workers are trained to use their lived experience intentionally to support others in their personal recovery journey.

Research distinguishes peer support from informal social support, with studies showing that structured peer support with clear boundaries produce measurable recovery related outcomes (Cooper et al, 2024; Puschner, 2025).

Peer support is free

While many of those delivering peer support in Scotland are unpaid this does not mean that peer support is free. Peer workers need training, support and supervision and ongoing development whether in paid or unpaid roles. There is also an increasing evidence base for the development of peer leadership structures to ensure that peer working maintains its fidelity and flourishes. This also ensures that there is peer leadership in strategy, service design and delivery.

The most definitive review of formal peer support implementation to date suggests that peer approaches are most likely to succeed where certain conditions are in place. These include training, peer supervision and, where peers are being integrated into wider teams, that there be a supportive, well informed and recovery orientated environment (Cooper et al, 2024).

Peer support is about fixing people

Peer support is about empowerment, not fixing or rescuing. Rather than providing answers or telling people what to do, peer support fosters self-determination by creating space for people to explore their own solutions, build confidence and reclaim control over their lives.

Studies of peer support focusing on outcomes related to self-determination and empowerment consistently demonstrate its effectiveness (see for example Mahike et al, 2017).

Peer support is inferior to clinical approaches

Peer support offers a different kind of support that can complement, rather than compete with traditional care and treatment approaches. It addresses social and emotional needs in ways that clinical models often can’t, especially for those who feel disconnected or misunderstood by formal systems. Peer support has the flexibility to work across sectors to provide early intervention and preventative ongoing support.

The distinctiveness of peer support, and its potential to complement the skills and practices of wider mental health practitioners, were described in a systemised review and expert consultation. This produced a typology of one-to-one peer support that included 16 components and eight sub-components, highlighting the complexity of the role. They outlined a mutual relationship rooted in shared lived experience which offers goal setting, emotional, social and practical support and has the ability to adapt to the cultural needs, values, background and context of people supported (Kotera et al, 2023).

Peer support needs clinical supervision

Peer support is fundamentally different from clinical care. Peer workers should be supervised by those with peer expertise. Supervisors who understand an approach based on lived experience and mutuality. Who can help ensure the effectiveness and maintain the fidelity of the role.

Consistent and well-informed supervision is regularly identified in research literature as being key to effective peer working (Reeves et al, 2023) and peer workers have emphasised the importance of having peer-led supervision (Byrne et al, 2022).

Peer support offers a different kind of support that can complement, rather than compete with traditional care and treatment approaches.

There is often a call for more evidence of the benefits of peer support and peer worker roles. Does peer support work? The simple answer is yes but its research is subject to multiple complexities.

What sort of peer support are we referring to? Individual or group based, how many sessions? Which peer support approaches are used and over how many sessions? What sort of evidence is being prioritised and how fitting are the methods to peer support?

Often decision makers prioritise evidence from randomised controlled trials when assessing the effectiveness of peer support. However, it is noteworthy that similar effectiveness data is not required when seeking to introduce psychiatrists, mental health nurses or psychologists to the workforce. Rather, we ask for evidence of the intervention of those professional groups, for example, medications or psychological methods.

What we do know from randomised controlled trials

Where well designed randomised controlled trials which focus on recovery specific outcomes are completed, they do show effects. For example the recent UPSIDES trials which tested peer support approaches in five countries, found beneficial impacts on empowerment, hope and elements of social inclusion among people with severe mental health conditions, despite the trials taking place during the coronavirus pandemic (Puschner et al, 2025).

Earlier trials tended to focus on more clinical outcomes like admissions and symptom reduction and as a result found less impressive outcomes. Early trials were also subject to numerous challenges in relation to their quality and reliability (Lloyd Evans et al, 2014; Pitt et al, 2013). However, at worst systematic reviews at that time suggested that peer workers were as effective as non-peer equivalents and are not associated with increased adverse events (Pitt et al, 2013).

There have in fact been at least 23 systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials of peer support working, giving some sense of the scope of the research (Cooper et al, 2024). One review, which included some group-based support, found it had a moderate effect on hope compared with the control group (Lloyd Evans et al, 2014). A later review found evidence for a modest but significant improvement in empowerment and self-reported recovery (White et al, 2020). Exceptions to the general rule that peer support does not impact clinical outcomes come from two reviews of perinatal mental health showing symptom reduction (Fang et al, 2022; Huang et al, 2020).

The person-centred nature of peer support may mean that there are meaningful outcomes for the service user which are not easily captured in standard outcome measurement tools or recognised as clinically significant.

(Cooper et al, 2024)

Wider evidence for peer support

While there is evidence from randomised controlled trials, acceptance of a wider range of research and lived experience evidence is vital if we are to better understand what helps mental health recovery.

Narrative research

Narrative studies of mental health recovery provide a wealth of evidence on the importance and value of support from others who have had similar experiences, and how it brings something different to that of traditional professional relationships (Slade et al, 2024).

Some healthcare professionals will have lived experience, but because of that power imbalance they can’t necessarily share with someone. It is that shared journey that is different to what other healthcare professionals can do or share.

(Stevenson, 2021)

Lived experience engagement and co-design

Scottish Recovery Network and many others have reported that engagement and co-design work with people living with mental health challenges consistently highlights the value placed on peer support and a desire for more peer roles in all types of mental health services and supports. Examples include the A Chance for Change report (Scottish Recovery Network, 2022) and With Us For Us report (VOX Scotland and Scottish Recovery Network, 2023).

Peer working tests of change

Evaluations of two peer working tests of change in Scotland highlighted how a different approach has resulted not only in high quality support for people but also better outcomes.

In NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, peer workers in Community Mental Health Teams supported 114 people between April 2021 and March 2022. 28% of people supported were living with depressive disorders, 17% had a diagnosis of personality disorder, 17% had experienced psychosis and 12% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The evaluation stated:

In sum, peer workers were able to use a variety of techniques and approaches in their work to support service users to gain a new understanding and to contribute to their recovery. Share lived experiences and the intentional use of recovery techniques were central to this. Peer workers seemed to foster an environment of trust, encouraging service users to be more open to trying different approaches. People using the services described this as fundamentally different to what they had experienced before.

Another evaluation of peer working in East Renfrewshire Health and Social Care Partnership noted:

The service was experienced as different by people using it. There was clear evidence that the peer approach and sharing of lived experience encouraged different types of conversation and that these could be a gateway to improved wellbeing…We saw evidence of strong relationships between people in receipt of services and peer workers. Relationships are often built upon lighter touch and informal conversations, which set the conditions for a high degree of trust and mutuality which in turn supported change. This relational practice emerged as a ‘golden thread’ across our analysis, helping to explain why this way of working was experienced so positively by those using the service. (Bradstreet & Cook, 2021).

UK and Ireland evaluations

Evidence that peer support works is not just confined to Scotland. A study of the employment of peer workers by HSE Ireland found that they modelled hope and improved people’s motivation as well as normalising mental health difficulties and reducing stigma. Those supported highlighted the particular value of peer workers in supporting them to find meaning in life, feel more in control of their life and reconnect with their community (Hunt & Byrne, 2019).

Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership Trust in England have implemented over 25 peer working roles in Community Mental Health Teams since 2021 and are planning to extend this to in-patient services. A review of peer working in the trust highlighted the role of peer workers in bringing hope, helping people to find meaning and purpose and also in normalising mental health experiences and reducing stigma (Dunkerley & Jordan, 2024).

Peer support can also play a role in recovering our struggling mental health system. In line with international guidance and best practice (World Health Organisation, 2021) there is acceptance that our current approach is not sustainable and that significant change is needed if we, as a society, are to successfully support those experiencing mental health challenges, enable recovery, and improve population wellbeing.

There have been many strategies and plans with shared policy aims but progress to achieving them has been very slow.

More money is of course important but it is also clear that despite previous investment in NHS mental health services and an increasing workforce, services are still under significant pressure and not able to meet need and demand. In the current financial climate there is evidence that much of the progress made is under threat from cuts to community-based and non-clinical services mostly delivered by third sector organisations.

The solution is often thought to lie in more money and mental health professionals. Remarkably, however, despite the amount of money spent on mental health care, the availability of mental health professionals in high income countries, or mental health research as currently imagined, the crisis has not eased. (Patel, 2023)

Lived experience and peer support brings fresh perspectives to mental health services opening up new conversations and therefore new solutions to the pressures faced

(Owen, Watson & Repper, 2024). Embracing lived experience/peer approaches across leadership, service design and service delivery helps us challenge the status quo which is not meeting the needs of the people of Scotland. These fresh perspectives enable innovation and new possibilities to emerge and give us the confidence to sit with the uncertainty needed to embrace and deliver much needed change.

Introducing peer workers into the mental health system has been shown to result in an increased focus on, and understanding of, recovery among other practitioners and managers (Ruiz-Perez G et al, 2025). The presence of people with lived experience in staff teams has also challenged stigma and resulted in a reduction in ‘them and us’ attitudes. This is reflected in the HSE Ireland study (Hunt & Byrne, 2019) where service providers stated that peer workers had enhanced the recovery orientation of services both in terms of thinking and practice and had enabled a better connection between service providers and those being supported.

Introducing peer workers into the mental health system has been shown to result in an increased focus on, and understanding of, recovery among other practitioners and managers.

(Ruiz-Perez G et al, 2025)

A recent study of peer working in mental health services in Germany (Ruiz-Perez G et al, 2025) found that working with peer workers increases other mental health practitioners use of lived experience insights in their practice. This results in them paying more attention to the circumstances or life contexts of those they are supporting, to adopt more strengths-based language and use diagnostic categories more flexibly. Embedding a peer workforce and the peer approach based on mutual sharing of experiences creates a contrast to the clinical nature and hierarchies within mental health services. It will increase access to recovery focused support for people seeking help and also open up opportunities for culture change.

This blog from a Lived Experience Practice and Peer Support Lead working in an NHS Trust in London highlights how peer workers not only act as role models of recovery but also recovery-focused working

So where are we with peer support and peer working in Scotland?

In 2024 Scottish Recovery Network commissioned The Big Scottish Peer Support Survey. (Stevenson, 2025).

The survey aim was to capture data on mental health and wellbeing peer support activity and the related workforce across the country. 105 peer support groups, services or activities completed the survey in full producing a robust snapshot of mental health peer support activity in Scotland in 2024.

What we found:

Peer support is available across Scotland and accessed by many people

There are mental health and wellbeing peer support groups, services and activities in every local authority area of Scotland. Areas with more than 10 groups or services include Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, East Lothian, Fife, West Lothian, Perth and Kinross, Renfrewshire and Scottish Borders. Most peer support groups and services operate across more than one local authority area.

85% of peer support groups and services are focused on delivery in Scotland with only a small number reporting some remote or online participants from outside Scotland.

Just over half (54%) of the peer support groups or services deliver peer support remotely or online including 5% who are fully remote or online.

Our survey revealed that at least 18,500 people participated in peer support in 2024.

Peer support groups and services highlighted that participating in peer support enabled people to have a safe space to talk and be heard without judgment, feel less isolated and build connections and a support network. These benefits are underpinned by peer support, particularly the shared lived experiences, mutual relationships and intentional space. This highlights the demand for peer support across Scotland and the significant role it plays in mental health support.

This level of activity demonstrates that we are not starting from scratch in Scotland. There is a wealth of peer support activity and peer innovation and expertise to build on and a clear demand for peer support.

People can access a wide range of peer support

Peer support is well placed and adaptable to meet the different needs of people from different communities of interest and experience. While most peer support groups and services have a focus on general mental health and wellbeing, a considerable number focus on particular population groups such as women, men, carers, people from minority ethnic groups or LGBTQIA+ groups. Some groups and services focus on experience such as particular mental health conditions, addiction, bereavement, parenting, neurodiversity, survivor of abuse, particular physical health conditions and disability.

Peer support offers choice and is developed in an inclusive, flexible and adaptive way. Most peer support groups and services offer more than one form of peer support, such as:

- in-person peer support groups (67%)

- one-to-one support provided by peers (55%)

- social peer-led support (35%)

- online support groups (34%) and

- text-based support, for example. through

email, forums or WhatsApp (27%)

Two-thirds of peer support groups and services are open access meaning that people can access peer support when they need it. In addition, more than half of peer support groups and services take referrals from other organisations, across sectors, providing opportunities for those supported by other services to access peer support.

Peer support is largely delivered by third sector organisations

A wide range of organisations manage and deliver peer support; from large third sector service providers to community-based health organisations and small, independent groups. Over 80% of those delivering peer support are, or are affiliated to, constituted third sector organisations, most of which have charitable status. This means that peer support exists in a framework provided by third sector or charity governance.

Overall one-third of peer support groups and services are wholly managed and delivered by peers and a further half are partly managed and delivered by peers. The most common sources of funding for peer support groups and services are:

- third sector organisations (33%)

- trusts and foundations (30%),

- Health and Social Care Partnerships (30%)

- Scottish Government (30%)

73% of paid and 90% of unpaid peer workers are employed in the third sector.

Smaller numbers had no source of funding (8%) and others attracted funding through local business sponsorship (8%) and earned income from, for example, room hire and participation fees. Over two-thirds of peer support groups and services have more than one source of funding with many attracting funding from multiple sources. This differs from many other countries where peer support has developed in public mental health services as well as in the third sector.

There is a peer workforce but it is largely unpaid

There are at least 235 paid and 1,155 unpaid peer workers in peer support groups and services across Scotland. These paid and unpaid peer workers often work alongside each other in distinctive but complementary roles in peer groups and services.

Peer support in Scotland is hard work but it is also so valuable and amazing. People working in this area are so passionate and motivated.

(Stevenson, 2025)

Around 60% of peer support groups and services employ paid peer workers. The average number of paid peer workers employed by these peer support groups or services is 3.5. Most paid peer workers are in front-line service delivery roles (197) with a small number involved in managerial or supervisory roles (38). While 60% of peer support groups and organisations employ paid peer workers, only 25% had peer workers in management or supervisory roles.

Around 60% of peer support groups and services work with unpaid peer workers; with the prevalence of unpaid peer workers being much higher in independent peer support groups and services than in those affiliated to large organisations. The average number of unpaid peer workers in these groups and organisations is 18.7. Most unpaid peer workers are in front-line service delivery roles (1,103) but there are a small number (52) in managerial or supervisory role. Our survey identified that at least 614 hours on unpaid peer worker support is being provided each week.

As most peer support is managed and delivered by the third sector, it is no surprise that the 73% of paid and 90% of unpaid peer workers are employed in the third sector. Only 20% of paid peer workers and 4% of unpaid peer workers are employed in the public sector in Scotland. Over 90% of peer support groups and organisations provide support for their peer workers (paid and unpaid) in some way. This is most commonly through informal support between peer workers, formal and informal supervision, reflective practice and training.

The dominance of unpaid peer workers differs from all other roles in mental health services and supports.

It also differs from the balance of paid and unpaid workers in other countries such as England, Republic of Ireland and Australia where there has been investment in lived experience leadership and a peer workforce in mental health services.

Peer support groups and organisations are facing many challenges

Most peer support groups and services reported that they had faced challenges in the past year. The challenges most often faced are related to funding/ fundraising and lack of understanding of peer support amongst decision-makers.

More funding to facilitate the growth of our service. We have high demand, but not enough capacity to deliver. (Stevenson, 2025)

Other challenges included meeting high demand for peer support, unpredictable attendance at peer support groups and recruiting, training and retaining volunteers. When asked what would help to sustain and grow peer support in Scotland the responses reflected these challenges and focused on influencing decision-makers on the value of peer support and increased and longer-term funding.

A cull of the dinosaurs with antiquated views towards peer support might work. In our experience it is sadly the case that peer support has no voice or value.

(Stevenson, 2025)

Assisting our partners to understand the value of peer support and the difference it makes to people.(Stevenson, 2025)

In Scotland there has been greater adoption of mental health peer worker roles in the third sector than in the public sector. As The Big Scottish Peer Support Survey tells us, many of these third sector roles are voluntary (unpaid) but there has been an increasing emphasis on the need for developing more paid peer roles.

Large service providers such as Penumbra and SAMH now employ paid peer workers in a range of community-based mental health services and have developed peer-led services such as Hope Point in Dundee and Sam’s Café in Fife. Many local mental health organisations now employ peer workers. This innovation has come from the third sector and been supported by a number of grant-makers and Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs).

This development has been in many ways ‘bottom up’ and happened in a policy context where there is weak commitment to mental health recovery and peer support at a national level. This has resulted in very limited development of recovery approaches including peer working in NHS mental health services.

The adoption of peer working, despite it being generally accepted as an indicator of a commitment to a recovery focused system, has lagged behind many other countries. These other countries (including England, Wales, Republic of Ireland, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Canada, Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand and the USA) see developing a peer workforce as part of a coherent strategy of culture change to embed recovery and lived experience in the mental health system.

The adoption of peer working, despite it being generally accepted as an indicator of a commitment to a recovery focused system, has lagged behind many other countries.

So why has there not been a commitment to peer support and peer working in Scottish public sector mental health services?

There is some history of interest in peer support as a way to enable the development of more recovery focused services and supports in Scotland. In 2008-2009 the Delivering for Mental Health Peer Support Worker Scheme, was piloted in a number of Health Boards across Scotland. The evaluation (McLean et al, 2009) concluded that the roll-out of peer working across mental health services in Scotland would be beneficial for those accessing support. They found that peer support worked well in a variety of settings, but that it was most successful where mental health teams were open to and practicing recovery orientated support.

Despite this positive evaluation and a commitment to peer working in the 2012 Mental Health Strategy the development of a peer workforce slipped from the policy agenda and progress has been ad hoc and very slow, particularly in the NHS. To understand why the commitment to peer working did not result in the development of peer working roles, Scottish Recovery Network commissioned research (Gordon & Bradstreet, 2015) to identify the enablers and barriers to peer support working in NHS mental health services.

It found that while the case for peer workers was generally well understood, implementation was seen as presenting significant challenges particularly with regard to:

- The absence of a clear policy driver and associated resources

- Concerns about definitions of professionalism and about the ability of wider multi-disciplinary teams to accept and integrate peer workers

- Limited commitment to recovery values and practice and to engagement with lived experience

These challenges have persisted. While there has been some progress made since 2014 this has largely been in the growth of peer support in the third sector. However recognition of peer support and the role of lived experience in mental health and suicide prevention at national and local level has increased to some extent in recent years. This can be seen in the actions to build peer support capacity in the Creating Hope Together Suicide Prevention Action Plan 2022 and to champion peer support across settings in the Mental Health and Wellbeing Delivery Plan 2023.

The Scottish Government and COSLA Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2023 set out a vision of a Scotland, free from stigma and inequality, where everyone fulfils their right to achieve the best mental health and wellbeing possible.

Embedding recovery and peer support in strategies, plans or legislative reforms gives it legitimacy and protection.

To achieve this the strategy recognised the need for ‘better informed policy, support, care and treatment, shaped by people with lived experience and practitioners, with a focus on recovery’ and a change in approach to ‘ensure that communities are better equipped to support people’s mental health and wellbeing and provide people with opportunities to connect with others’.

A range of priorities were identified including promoting a whole system, whole person approach; expanding and improving support through the national approach on Time Space Compassion and ensuring that people receive the quality of support required, when and where they need it to promote recovery.

The Heath and Social Care Service Renewal Framework 2025-2035 sets out major areas for change to deliver on policy goals including those in the Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. These include a commitment to an early intervention and prevention approach and delivering care that is ‘people-led and value based’. This framework and the Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy and Delivery Plan provide a policy framework for embracing recovery and peer support but, as yet, any steps towards this appear tentative.

When considering the experience of peer support development in other countries a number of key catalysts for change are apparent. These highlight what is needed to establish the conditions for recovery and peer support to contribute to the cultural change needed if we are to achieve our mental health and wellbeing policy aims in Scotland.

These countries have access to the same international evidence base for mental health recovery and peer support that Scotland has. When considering the catalysts for change in other countries it is clear that traditional evidence of the impacts of peer support as shared in this report was not a decisive factor. The drivers were related to the acknowledgement of the need for change in the mental health system and the adoption of recovery as a guiding principle, setting the direction of travel. This led to a focus on rights, relational practice and the need to effectively centre lived experience in all aspects of mental health policy, service design and service delivery.

Mental health recovery and peer support are embedded in strategies, plans and legislative reform

Embedding recovery and peer support in strategies, plans or legislative reforms gives it legitimacy and protection. This enables peer support to be seen as central rather than discretionary. It shifts peer support from a ‘nice to have’ addition to a core workforce and system change approach.

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System (Australia, 2021) created lived experience roles across governance, delivery and system oversight which unlocked significant structural change. Actions 18 and 19 of the Health Education and Improvement Wales and Social Care Wales Workforce Plan has given peer support formal recognition. In England the NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan (2019) contained plans to increase the mental health peer workforce from 530 to over 4,700 and this has resulted in a significant increase in the number of peer workers across trusts in community, in-patient and specialist services.

There are visible peer or lived experience leaders in the system at all levels

Visible and senior leaders of peer support, particularly those with roles in government or service leadership act as change agents across the system. They do more than deliver services, they advocate, mentor, design policy and model new forms of leadership. They can help overcome resistance, broker trust and create legitimacy.

Leaders like Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, former Prime Minister of Denmark and founder of DetSociale Netvaerk, Maggie Toko, Consumer Commissioner Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission Victoria Australia and Julie Repper, Director ImROC have helped to elevate peer support from front-line service delivery to a whole-system influence.

In many countries including England, Australia, Ireland, Denmark and USA there has been investment in lived experience lead roles in government, mental health service management and in services. These roles are varied but are often at a level where they can inform policy and practice and increasingly have a focus on co-production approaches facilitating wider lived experience engagement in policy development, service design and review.

Peer support is seen as a driver of cultural change not just a service

Where countries and organisations have embraced mental health recovery and peer values (such as mutuality, choice, hope, rights) they have used peer support to challenge paternalism, to centre lived experience and model trauma-informed, rights-based approaches.

In Victoria Australia, peer support was reframed as a mechanism to drive human rights-based reform throughout the mental health system. NHS Trusts in England used peer-led recovery colleges to shift service culture. In Ireland the HSE established the Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office to drive a programme of recovery change including co-production with lived experience and the implementation of paid peer worker roles.

International exchange and collaboration helps build credibility and shift mindsets

Countries often drew explicitly on international approaches and expertise to legitimise their own work or fast-track development. This included bringing well-respected leaders from abroad, sharing frameworks and referencing international evidence which helped accelerate progress, build credibility and shift mindsets.

Ireland invited peer leaders from England and Aotearoa New Zealand to unlock backing for peer support and support its early implementation. Wales drew on frameworks and insights from England’s recovery college network. Victoria Australia referenced Aotearoa New Zealand’s peer-led crisis models in shaping their future direction and frequently draw on international relationships to shape strategy and practice.

There is much to reflect on and learn from the experience of other countries. Indeed these catalysts are recognised by those involved in mental health recovery and peer support in Scotland. Participants in the Growing Peer Support in Scotland community roundtables held in February and March 2025 were clear that to grow peer support in Scotland we need a clear national policy commitment to embedding peer support and peer/lived experience leadership in mental health and for there to be a collaborative approach to developing and implementing actions to make this happen.

Peer support is a valuable commodity that I don’t think is taken seriously enough.

(Stevenson, 2025)

We hope that Insight Report 1 is informative and inspiring. It is the first of four Insight Reports on themes relating to peer support in Scotland. We all have a part to play in creating the change needed in our mental health system to ensure that lived experience is centred, peer support embedded and people are supported to recover and live good lives of their choosing.

A call to action

This report is designed to inform, inspire, and influence change. Here are practical ways you can use it now:

If you are a decision maker, civil servant or politician

- Quote findings in parliamentary questions, debates, and briefings

- Champion peer support as a policy priority

If you are a funder

- Share the report with your board or team as evidence of need

- Review funding criteria to ensure peer-led projects are supported

- Explore opportunities for long-term, sustainable investment

If you are a service designer or provider

- Discuss the report in team meetings or planning sessions

- Identify where peer roles could be introduced or strengthened

- Involve people with lived experience in co-designing services

If you are part of a community or peer support group

- Use the report to advocate for local funding or recognition

- Share stories and experiences that align with the findings

- Connect with others to build a stronger collective voice

Everyone can

- Share the report widely across networks and social media

- Host a discussion event or workshop using the findings

- Add your voice: write to local representatives about the importance of peer support

Together, we can make peer support a central part of Scotland’s mental health system.

The Future is Peer

Anthony W A (1993) Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s.

Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11-23 https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-46756-001

Bipolar Scotland https://bipolarscotland.org. uk/

Bradstreet S & Cook A (2021) Evaluation of the Peer Support Test of Change EastRenfrewshire Health and Social Care Partnership, Matter of Focus

Bradstreet S & Akisanya-Ali A (2022) NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Mental Health Peer Support Worker Test of Change Evaluation, Matter of Focus

Bradstreet S & Buelo A (2023). ImROC Peer Support Theory and Practice Training: An independent evaluation, Matter of Focus

Byrne L, Roennfeldt H, Wolf J, Linfoot A, Foglesong D, Davidson L, & Bellamy C (2022) Effective Peer Employment Within Multidisciplinary Organizations: Model for Best Practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 49(2), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01162-2

Cooper R E, Saunders K R K, Greenburgh A, Shah P, Appleton R, Machin K, Jeynes T, Barnett P, Allan S M, Griffiths J, Stuart R, Mitchell L, Chipp B, Jeffreys S, Lloyd-Evans B, Simpson A, & Johnson S (2024). The effectiveness, implementation, and experiences of peer support approaches for mental health: a systematic umbrella review. BMC Medicine, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03260-y

Davidson L, O’Connell M J, Tondora J, Lawless M, & Evans A C (2005) Recovery in serious mental illness: A new wine or just a new bottle? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(5), 480–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.480

Davidson L, Bellamy C, Kimberly G, & Miller R (2012) Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 2(11), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

DET Sociale Netvaerk https://detsocialenetvaerk.dk/

Dunkerley L & Jordan M (2024) The Roles,Responsibilities and Tasks of Peer SupportWorkers in Coventry and WarwickshirePartnership Trust: A Service Review. ImROC

ImROC England NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan (2019) https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-mental-health-implementation-plan-2019-20-2023-24/

Fang Q, Lin L, Chen Q, Yuan Y, Wang S, Zhang Y, Liu T, Cheng H, & Tian L (2022) Effect of peer support intervention on perinatal depression: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 74, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.12.001

George L C, O’Hagan M, Bradstreet S, & Burge M (2016) The emerging field of peer support within mental health services. In M Smith& A Jury (Eds), Workforce Development Theory and Practice in the Mental Health Sector (pp. 222–250). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1874-7.ch011

Gillard S, Foster R, Gibson S, Goldsmith L, Marks J, & White S (2017) Describing a principles-based approach to developing and evaluating peer worker roles as peer support moves into mainstream mental health services https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-03-2017-0016

Gordon J & Bradstreet S (2015) So if we like the idea of peer support workers, why aren’t we seeing more? World Journal of Psychiatry22; 5(2): 160-6

Habitus Collective and Scottish Recovery Network (2025) Growing Peer Support in Scotland: Community Roundtable Summary Report. Scottish Recovery Network

Habitus Collective (2025) Peer Support Without Borders https://scottishrecovery.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Peer-Support-Without-Borders.pdf HEIW & Social Care Wales, Strategic Mental Health Workforce Plan for Health and Social Care: Implementation Plan (2023-2025) https://heiw.nhs.wales/files/mh-final-implementation-plan-may-2023

Hope Point, Dundee (Penumbra Mental Health) https://penumbra.org.uk/services/hope-point-dundee-wellbeing-support/

HSE Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/mental-health-engagement-and-recovery/

Huang R, Yan, C, Tian Y, Lei B, Yang D, Liu D, Lei J (2020) Effectiveness of peer support intervention on perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Journal of Affective Disorders 276 (2) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.048

Hunt & Byrne (2019) Peer support workersin mental health services: a report on theimpact of peer support workers in mental health services. HSE Ireland

ImROC https://www.imroc.org/about-us

Kotera Y, Newby C, Charles A, Ng F, Watson E, Davidson L, Nixdorf R, Bradstreet S, Brophy L, Brasier C, Simpson A, Gillard S, Puschner B, Kidd S A, Mahlke C, Sutton A J, Gray L J, Smith E A, Ashmore A, Pomberth S & Slade, M. (2023). Typology of Mental Health Peer Support Work Components: Systematised Review and Expert Consultation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 23, 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01126-7

Leamy M, Bird V, le Boutillier C, Williams J, & Slade M (2011) Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp. bp.110.083733

Lloyd-Evans B, Mayo-Wilson E, Harrison B, Istead H, Brown E, Pilling S, Johnson S, & Kendall T (2014) A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 1–12. https:// doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-39

Mahlke C I, Priebe S, Heumann K, Daubmann A, Wegscheider K, & Bock T (2017) Effectiveness of one-to-one peer support for patients with severe mental illness – a randomised controlled trial. European Psychiatry, 42, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.007

Mead S, Hilton D, & Curtis L (2001) Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0095032

McLean J, Biggs H, Whitehead I, Pratt R & Maxwell M (2009) Evaluation of the Delivering for Mental Health Peer Support Worker Scheme, Scottish Government SocialResearch Findings No. 87/2009

Owen, D, Watson, E., & Repper, J. (2024) – The role of lived experience within health and social care systems – ImROC Briefing Paper 26.

Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Kohrt B, Kieling C, Sunkel C, Kola L, Chang O, Charlson F, O’Neill K, Herrman H (2023) Transforming mental health systems globally: principles and policy recommendations. Lancet. 19;402(10402):656-666. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00918-2

Pitt V, Lowe D, Hill S, Prictor M, Hetrick S E, Ryan R, & Berends L (2013) Consumer-providers of care for adult clients of statutory mental health services. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004807.pub2

Puschner B, Nakku J, Hiltensperger R et al (2025) Effectiveness of peer support for people with severe mental health conditions in high-, middle- and low-income countries: multicentre randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–9. https://doi. org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10299

Reeves V, Loughhead M, Halpin M A, & Procter N (2023) Organisational Actions for Improving Recognition, Integration and Acceptance of Peer Support as Identified by a Current Peer Workforce. Community Mental Health Journal, 60(1), 169–178. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10597-023-01179-x

Repper J & Perkins R (2006) Social Inclusion and Recovery: A Model for Mental Health Practice. Bailliere Tindall, UK. ISBN0-7020-2601-8

Ruiz-Pérez G, Küsel M, von Peter S (2025) Changes in attitudes of mental health care staff surrounding the implementation of peer support work: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 20(4): e0319830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0319830

Sam’s Café Fife (SAMH) https://www.samscafe.org.uk/

Scottish Government and COSLA Creating Hope Together, Suicide Prevention Action Plan (2022-2025) https://www.gov.scot/publications/creating-hope-together-scotlands-suicide-prevention-action-plan-2022-2025/

Scottish Government and COSLA Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy (2023) https://www.gov.scot/publications/mental-health-wellbeing-strategy/

Scottish Government Health and Social Care Service Renewal Framework (2025-2035) https://www.gov.scot/publications/health-social-care-service-renewal-framework/

Scottish Government Mental Health Strategy for Scotland (2012-2015) https://www.gov.scot/publications/mental-health-strategy-scotland-2012-2015/

Scottish Recovery Network (2022) A Chance for Change https://scottishrecovery.net/resources/a-chance-for-change

Scottish Recovery Network (2013) Reviewing Peer Working: A New Way of working in Mental Health

Simpson A, Quigley J, Henry S J, & Hall C (2014) Evaluating the selection, training, and support of peer support workers in the United Kingdom. In Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services (Vol. 52, Issue 1, p. 31). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24305905/

Slade et al (2014) Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of online recorded recovery narratives in improving quality of life for people with non-psychotic mental health problems: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial, World Psychiatry 23(1): 101-112 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wps.21176

Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, Hamilton B, O’Hagan M, Panther G, Perkins R, Shepherd G, Tse S, Whitley R (2014) Uses and abuses of recovery: implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems, World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12-20. https://doi. org/10.1002/wps.20084

Solomon P (2004) Peer Support/Peer Provided Services Underlying Processes, Benefits, and Critical Ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4), 392–401. https://doi. org/10.2975/27.2004.392.401

Stevenson (2021) What makes peer support unique. A Report for Scottish Recovery Network (unpublished)

Stevenson (2025) The Big Scottish Peer Support Survey. A report for Scottish Recovery Network https://scottishrecovery.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/The-Big-Scottish-Peer-Support-Survey-reportMay2025.pdf

The Neuk Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Centre https://anchorhouseperth.org/find-help-at-the-neuk-crisis-support-guidance/

Victoria’s Government, Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission Victoria, Australia https://www.mhwc.vic.gov.au/mhwc-leadership

Victoria’s Government, The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Menal Health System- final report (2021) https://www.vic.gov.au/royal-commission-victorias-mental-health-system-final-report

Vox Scotland and Scottish Recovery Network, With Us For Us report (2023) https://scottishrecovery.net/resources/with-us-for-us/

Watson E (2017) The mechanisms underpinning peer support: a literature review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(6), 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417559

White S, Foster R, Marks J, Morshead R, Goldsmith L, Barlow S, Sin J, & Gillard S (2020) The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02923-3

World Health Organisation (2021) Peer support mental health services: Promoting person-centred and rights-based approaches

World Health Organisation (2022) World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all

Yim C S T, Chieng J H L, Tang X R, Tan J X, Kwok V K F, & Tan S M (2023) Umbrella review on peer support in mental disorders. International Journal of Mental Health, 52(4), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2023.2166444